- Home

- Tom Sharpe

The Wilt Alternative Page 3

The Wilt Alternative Read online

Page 3

Irmgard’s face was not simply beautiful. In spite of the beer Wilt might have withstood the magnetism of mere beauty. He was defeated by the intelligence of her face. In fact there were imperfections in that face from a purely physical point of view. It was too strong for one thing, the nose was a shade retroussé to be commercially perfect, and the mouth too generous, but it was individual, individual and intelligent and sensitive and mature and thoughtful and … Wilt gave up the addition in despair and as he did so it seemed to him that Irmgard was gazing down into his two adoring eyes, or anyway into the binoculars, and that a subtle smile played about her gorgeous lips. Then she turned away and went back into the flat. Wilt dropped the binoculars and reached trancelike for the beer bottle. What he had just seen had changed his view of life.

He was no longer Head of Liberal Studies, married to Eva, the father of four quarrelsome repulsive daughters, and thirty-eight. He was twenty-one again, a bright, lithe young man who wrote poetry and swam on summer mornings in the river and whose future was alight with achieved promise. He was already a great writer. The fact that being a writer involved writing was wholly irrelevant. It was being a writer that mattered and Wilt at twenty-one had long since settled his future in advance by reading Proust and Gide, and then books on Proust and Gide and books about books on Proust and Gide, until he could visualize himself at thirty-eight with a delightful anguish of anticipation. Looking back on those moments he could only compare them to the feeling he now had when he came out of the dentist’s surgery without the need for any fillings. On an intellectual plane, of course. Spiritual, with smoke-filled, cork-lined rooms and pages of illegible but beautiful prose littering, almost fluttering from, his desk in some deliciously nondescript street in Paris. Or in a white-walled bedroom on white sheets entwined with a tanned woman with the sun shining through the shutters and shimmering on the ceiling from the azure sea somewhere near Hyères. Wilt had tasted all these pleasures in advance at twenty-one. Fame, fortune, the modesty of greatness, bons mots drifting effortlessly from his tongue over absinthe, allusions tossed and caught, tossed back again like intellectual shuttlecocks, and the intense walk home through dawn-deserted streets in Montparnasse.

About the only thing Wilt had eschewed from his borrowings off Proust and Gide had been small boys. Small boys and plastic dustbins. Not that he could see Gide buggering about brewing beer anyway, let alone in plastic dustbins. The sod was probably a teetotaller. There had to be some deficit to make up for the small boys. So Wilt had lifted Frieda from Lawrence while hoping to hell he didn’t get TB, and had endowed her with a milder temperament. Together they had lain on the sand making love while the ripples of the azure sea broke over them on an empty beach. Come to think of it, that must have been about the time he saw From Here to Eternity and Frieda had looked like Deborah Kerr. The main thing was she had been strong and firm and in tune, if not with the infinite as such, with the infinite variations of Wilt’s particular lusts. Only they hadn’t been lusts. Lust was too insensitive a word for the sublime contortions Wilt had had in mind. Anyway, she had been a sort of sexual muse, more sex than muse, but someone to whom he could confide his deepest perceptions without being asked who Rochefou … what’s-his-name was, which was about as near being a blasted muse as Eva ever got. And now look at him, lurking in a bleeding Spockery drinking himself into a beer belly and temporary oblivion on something pretending to be lager that he’d brewed in a plastic dustbin. It was the plastic that got Wilt. At least a dustbin was appropriate for the muck but it could have had the dignity of being a metal one. But no, even that slight consolation had been denied him. He’d tried one and had damned near poisoned himself. Never mind that. Dustbins weren’t important and what he had just seen had been his Muse. Wilt endowed the word with a capital M for the first time in seventeen disillusioning years and then promptly blamed the bloody lager for this lapse. Irmgard wasn’t a muse. She was probably some dumb, handsome bitch whose Vater was Lagermeister of Cologne and owned five Mercedes. He got up and went into the house.

When Eva and the quads returned from the theatre he was sitting morosely in front of the television ostensibly watching football but inwardly seething with indignation at the dirty tricks life played on him.

‘Now then you show Daddy how the lady danced,’ said Eva, ‘and I’ll put the supper on.’

‘She was ever so beautiful, Daddy,’ Penelope told him. ‘She went like this and there was this man and he …’ Wilt had to sit through a replay of The Rite of Spring by four small lumpish girls who hadn’t been able to follow the story anyway and who took turns to try to do a pas de chat off the arm of his chair.

‘Yes, well, I can see she must have been brilliant from your performance,’ said Wilt. ‘Now if you don’t mind I want to see who wins …’

But the quads took no notice and continued to hurl themselves about the room until Wilt was driven to take refuge in the kitchen.

‘They’ll never get anywhere if you don’t take an interest in their dancing,’ said Eva.

‘They won’t get anywhere anyway if you ask me, and if you call that dancing I don’t. It’s like watching hippos trying to fly. They’ll bring the bloody ceiling down if you don’t look out.’

Instead Emmeline banged her head on the fireguard and Wilt had to put a blob of Savlon on the scratch. To complete the evening’s miseries Eva announced that she had asked the Nyes round after supper.

‘I want to talk to him about the Organic Toilet. It’s not working properly.’

‘I don’t suppose it’s meant to,’ said Wilt. ‘The bloody thing is a glorified earth closet and all earth closets stink.’

‘It doesn’t stink. It has a composty smell, that’s all, but it doesn’t give off enough gas to cook with and John said it would.’

‘It gives off enough gas to turn the downstairs loo into a death-chamber if you ask me. One of these days some poor bugger is going to light a cigarette in there and blow us all to Kingdom Come.’

‘You’re just biased against the Alternative Society in general,’ said Eva. ‘And who was it who was always complaining about my using chemical toilet cleaner? You were. And don’t say you didn’t.’

‘I have enough trouble with society as it is without being bunged into an alternative one, and, while we are on the subject, there must be an alternative to poisoning the atmosphere with methane and sterilizing it with Harpic. Frankly I’d say Harpic had something to recommend it. At least you could flush the bloody stuff down the drain. I defy anyone to flush Nye’s filthy crap-digester with anything short of dynamite. It’s a turd-encrusted drainpipe with a barrel at the bottom.’

‘It has to be like that if you’re going to put natural goodness back into the earth.’

‘And get food poisoning,’ said Wilt.

‘Not if you compost it properly. The heat kills all the germs before you empty it.’

‘I don’t intend to empty it. You had the beastly thing installed and you can risk your life in the cellar disgorging it when it’s good and ready. And don’t blame me if the neighbours complain to the Health Department again.’

They argued on until supper and Wilt took the quads up to bed and read them Mr Gumpy for the umpteenth time. By the time he came down the Nyes had arrived and were opening a bottle of stinging-nettle wine with an alternative corkscrew John Nye had fashioned from an old bedspring.

‘Ah, hullo Henry,’ he said with that bright, almost religious goodwill which all Eva’s friends in the Self-Sufficiency world seemed to affect. ‘Not a bad vintage, 1976, though I say it myself.’

‘Wasn’t that the year of the drought?’ asked Wilt.

‘Yes, but it takes more than a drought to kill stinging-nettles. Hardy little fellows.’

‘Grow them yourself?’

‘No need to. They grow wild everywhere. We just gathered them from the wayside.’

Wilt looked doubtful. ‘Mind telling which side of the way you harvested this particular cru?’

‘As far as I

remember it was between Ballingbourne and Umpston. In fact, I’m sure of it.’ He poured a glass and handed it to Wilt.

‘In that case I wouldn’t touch the stuff myself,’ said Wilt, handing it back. ‘I saw them cropspraying there in 1976. These nettles weren’t grown organically. They’ve been contaminated.’

‘But we’ve drunk gallons of the wine,’ said Nye. ‘It hasn’t done us any harm.’

‘Probably won’t feel the effects until you’re sixty,’ said Wilt, ‘and then it will be too late. It’s the same with fluoride, you know.’

And having delivered himself of this dire warning he went through to the lounge, now rechristened by Eva the ‘Being Room’, and found her deep in conversation with Bertha Nye about the joys and deep responsibilities of motherhood. Since the Nyes were childless and lavished their affection on humus, two pigs, a dozen chickens and a goat, Bertha was receiving Eva’s glowing account with a stoical smile. Wilt smiled stoically back and wandered out through the french windows to the summerhouse and stood in the darkness looking hopefully up at the dormer window. But the curtains were drawn. Wilt sighed, thought about what might have been and went back to hear what John Nye had to say about his Organic Toilet.

‘To make the methane you have to maintain a steady temperature, and of course it would help if you had a cow.’

‘Oh, I don’t think we could keep a cow here,’ said Eva. ‘I mean we haven’t the ground and …’

‘I can’t see you getting up at five every morning to milk it,’ said Wilt, determined to put a stop to the awful possibility that 9 Willington Road might be turned into a smallholding. But Eva was back on the problem of the methane conversion.

‘How do you go about heating it?’ she asked.

‘You could always install solar panels,’ said Nye. ‘All you need are several old radiators painted black and surrounded with straw and you pump water through them …’

‘Wouldn’t want to do that,’ said Wilt. ‘We’d need an electric pump and with the energy crisis what it is I have moral scruples about using electricity.’

‘You don’t need to use a significant amount,’ said Bertha. ‘And you could always work a pump off a Savonius rotor. All you require are two large drums …’

Wilt drifted off into his private reverie, awakening from it only to ask if there was some way of getting rid of the filthy smell from the downstairs loo, a question calculated to divert Eva’s attention away from Savonius rotors, whatever they were.

‘You can’t have it every way, Henry,’ said Nye. ‘Waste not want not is an old motto, but it still applies.’

‘I don’t want that smell,’ said Wilt. ‘And if we can’t produce enough methane to burn the pilot light on the gas stove without turning the garden into a stockyard, I don’t see much point in wasting time stinking the house out.’

The problem was still unresolved when the Nyes left.

‘Well, I must say you weren’t very constructive,’ said Eva as Wilt began undressing. ‘I think those solar radiators sound very sensible. We could save all our hot-water bills in the summer and if all you need are some old radiators and paint …’

‘And some damned fool on the roof fixing them there. You can forget it. Knowing Nye, if he stuck them up there they’d fall off in the first gale and flatten someone underneath, and anyway with the summers we’ve had lately we’d be lucky to get away without having to run hot water up to them to stop them freezing and bursting and flooding the top flat.’

‘You’re just a pessimist,’ said Eva, ‘you always look on the worst side of things. Why can’t you be positive for once in your life?’

‘I’m a ruddy realist,’ said Wilt. ‘I’ve come to expect the worst from experience. And when the best happens I’m delighted.’

He climbed into bed and turned out the bedside lamp. By the time Eva bounced in beside him he was pretending to be asleep. Saturday nights tended to be what Eva called Nights of Togetherness, but Wilt was in love and his thoughts were all about Irmgard. Eva read another chapter on Composting and then turned her light out with a sigh. Why couldn’t Henry be adventurous and enterprising like John Nye? Oh well, they could always make love in the morning.

But when she woke it was to find the bed beside her empty. For the first time since she could remember Henry had got up at seven on a Sunday morning without being driven out of bed by the quads. He was probably downstairs making her a pot of tea. Eva turned over and went back to sleep.

*

Wilt was not in the kitchen. He was walking along the path by the river. The morning was bright with autumn sunlight and the river sparkled. A light wind ruffled the willows and Wilt was alone with his thoughts and his feelings. As usual his thoughts were dark while his feelings were expressing themselves in verse. Unlike most modern poets Wilt’s verse was not free. It scanned and rhymed. Or would have done if he could think of something that rhymed with Irmgard. About the only word that sprang to mind was Lifeguard. After that there was yard, sparred, barred and lard. None of them seemed to match the sensitivity of his feelings. After three fruitless miles he turned back and trudged towards his responsibilities as a married man. Wilt didn’t want them.

4

He didn’t much want what he found on his desk on Monday morning. It was a note from the Vice-Principal asking Wilt to come and see him at, rather sinisterly, ‘your earliest, repeat earliest, convenience’.

‘Bugger my convenience,’ muttered Wilt. ‘Why can’t he say “immediately” and be done with it?’

With the thought that something was amiss and that he might as well get the bad news over and done with as quickly as possible, he went down two floors and along the corridor to the Vice-Principal’s office.

‘Ah Henry, I’m sorry to bother you like this,’ said the Vice-Principal, ‘but I’m afraid we’ve had some rather disturbing news about your department.’

‘Disturbing?’ said Wilt suspiciously.

‘Distinctly disturbing. In fact all hell has been let loose up at County Hall.’

‘What are they poking their noses into this time? If they think they can send any more advisers like the last one we had who wanted to know why we didn’t have combined classes of bricklayers and nursery nurses so that there was sexual equality you can tell them from me …’

The Vice-Principal held up a protesting hand. ‘That has nothing to do with what they want this time. It’s what they don’t want. And, quite frankly, if you had listened to their advice about multi-sexed classes this wouldn’t have happened.’

‘I know what would have,’ said Wilt. ‘We’d have been landed with a lot of pregnant nannies and –’

‘If you would just listen a moment. Never mind nursery nurses. What do you know about buggering crocodiles?’

‘What do I know about … did I hear you right?’

The Vice-Principal nodded. ‘I’m afraid so.’

‘Well, if you want a frank answer I shouldn’t have thought it was possible. And if you’re suggesting …’

‘What I am telling you, Henry, is that someone in your department has been doing it. They’ve even made a film of it.’

‘Film of it?’ said Wilt, still grappling with the appalling zoological implications of even approaching a crocodile, let alone buggering the brute.

‘With some apprentice class,’ continued the Vice-Principal, ‘and the Education Committee have heard about it and want to know why.’

‘I can’t say I blame them,’ said Wilt. ‘I mean you’d have to be a suicidal candidate for Krafft-Ebing to proposition a fucking crocodile and while I know I’ve got some demented sods as part-timers I’d have noticed if any of them had been eaten. Where the hell did he get the crocodile from?’

‘No use asking me,’ said the Vice-Principal. ‘All I know is that the Committee insist on seeing the film before passing judgement.’

‘Well, they can pass what judgements they like,’ said Wilt, ‘just so long as they leave me out of it. I accept no responsibility fo

r any filming that’s done in my department and if some maniac chooses to screw a crocodile, that’s his business, not mine. I never wanted all those TV cameras and cines they foisted on to us. They cost a fortune to run and some damned fool is always breaking the things.’

‘Whoever made this film should have been broken first if you ask me,’ said the Vice-Principal. ‘Anyway, the Committee want to see you in Room 80 at six and I’d advise you to find out what the hell has been going on before they start asking you questions.’

Wilt went wearily back to his office desperately trying to think which of the lecturers in his department was a reptile-lover, a follower of nouvelle vague brutalism in films and clean off his rocker. Pasco was undoubtedly insane, the result, in Wilt’s opinion, of fourteen years’ continuous effort to get Gasfitters to appreciate the linguistic subtleties of Finnegans Wake, but although he had twice spent a year’s medical sabbatical in the local mental hospital he was relatively amiable and too hamfisted to use a cine-camera, and as for crocodiles … Wilt gave up and went along to the Audio-Visual Aid room to consult the register.

‘I’m looking for some blithering idiot who’s made a film about crocodiles,’ he told Mr Dobble, the AVA caretaker. Mr Dobble snorted.

‘You’re a bit late. The Principal’s got that film and he’s carrying on something horrible. Mind you, I don’t blame him. I said to Mr Macaulay when it came back from processing, “Blooming pornography and they pass that through the labs. Well I’m not letting that film out of here until it’s been vetted.” That’s what I said and I meant it.’

‘Vetted being the operative word,’ said Wilt caustically. ‘And I don’t suppose it occurred to you to let me see it first before it went to the Principal?’

‘Well, you don’t have no control over the buggers in your department, do you Mr Wilt?’

‘And which particular bugger made this film?’

‘I’m not one for naming names but I will say this, Mr Bilger knows more about it than meets the eye.’

Blott on the Landscape

Blott on the Landscape Porterhouse Blue

Porterhouse Blue The Wilt Alternative:

The Wilt Alternative: The Great Pursuit

The Great Pursuit Ancestral Vices

Ancestral Vices The Midden

The Midden Vintage Stuff

Vintage Stuff The Throwback

The Throwback Grantchester Grind:

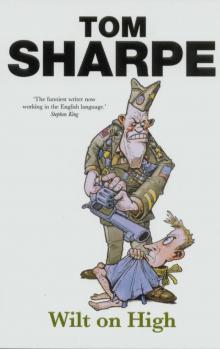

Grantchester Grind: Wilt on High:

Wilt on High: Riotous Assembly

Riotous Assembly Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Gropes

The Gropes Wilt in Nowhere:

Wilt in Nowhere: The Wilt Inheritance

The Wilt Inheritance Wilt:

Wilt: The Wilt Alternative

The Wilt Alternative The Wilt Alternative w-2

The Wilt Alternative w-2 Grantchester Grind

Grantchester Grind Wilt on High

Wilt on High Wilt w-1

Wilt w-1 Wilt

Wilt The Wilt Inheritance (2010)

The Wilt Inheritance (2010) Wilt in Nowhere

Wilt in Nowhere Wilt in Nowhere w-5

Wilt in Nowhere w-5 Wilt on High w-3

Wilt on High w-3